|

|

Making the impossible phone was easier than it sounds because my friend, fellow EFFer and campmate John Gilmore has a 2-way satellite internet connection (from Tachyon), and brings the dish to Burning Man to share it. Starting in 2005, John helped finance a microwave link shared with the Burning Man organization. Others in my camp (known as the Embassy) such as Clif Cox and Paul Traina build an 802.11 wireless network. So packets can be gotten to the world, though with some lag time.

|

| All assembled |

Since I've recently been developing software in the Voice over Internet space, I had the tools to set up a phone connection. However, I wasn't the first. The earliest claim of a phone I know of comes from Tsutomu who, with the use of a directional antenna, tower and an possibly illegal amplifier, was able to connect to cell towers 90 miles away in Winnemucca. Peter Shipley did similar experiments, as I recall. Matt Peterson of the EFF reports doing H.323 based phone experiments in 2001.

Of course, satellite phones work in the desert, though they are expensive. A rumour, never confirmed, suggested that one participant in 2003 was carrying one and selling time on it (a violation of the non-commercial rules of the event.)

In 2003, I and others tried Voice over IP experiments. At least 2 Vonage phone adapters were brought. I brought a Grandstream IP phone and tweaked it to use less bandwith. This was just left on the table in camp, and a number of people came in and used the phones, though they were not promoted to the public. When I looked at the logs, I was amused to see that many people had used calling-cards to make their calls, not understanding the phone was free.

There have been a number of fake phone booths and fake phones at Burning Man. One popular one, dating back to 1997, was a motorized end-table with a phone. It would drive up to people on the desert (under remote control) and the phone would ring, and the hidden driver would talk to you. Phone booths connecting two parts of Burning Man have also been fun.

Popular in 2003 was the "Talk to God" phonebooth. This oversized fake booth contained a phone connected to a semi-hidden person in a nearby camp, who would pretend to be God through a voice disguiser.

|

| The guts |

I approached fellow camp-member Brent Chapman, who is known to many as the author of the Majordomo mailing list software and a popular firewall book, about a phone project. He acquired an old authentic Western Electric pay-phone, along with pedestal and enclosure. While a real booth would have been nice, as noted they are a bit more expensive to ship than a lark project justifies. Had we found one in California, that would have made it easier. They can also be hand-built. The old booths with folding doors are cheap because they are no longer wheelchair compliant.

The goal was to make the phone battery powered and wireless so it could be placed anywhere, and in fact moved once or twice during the event. The physicality of it is a large part of the art of it. While one could, for example, just bring a wireless VoIP phone such as the one sold by my friend Jeff Pulver, that looks and acts a lot like a cell phone, and there is no cognitive dissonance in seeing that it works. We expect small handheld devices to be wireless and work in remote places today. (I will have such a phone, as Jeff is loaning me one for experiments.)

|

| Making first call |

There is an instructions page at a URL printed on the phone. However, by and large it is just used like any other phone, pick it up and dial.

Here's a photo of the first call we made plugging the phone booth into the SIP adapter. My main concern was whether the adapter would be able to ring the old-style bell in the phone which is a real physical bell. This box was designed long after phones switched to virtual bells, which take less power. It was able to do it.

|

| In Pedestal |

To connect the phone, I would need what's called an "Analog Terminal Adapter" or ATA. These are made by companies like Cisco, Grandstream, Sipura and others, and used by the new broadband phone companies like Vonage and Broadvoice. They have an Ethernet jack on one side and a phone jack on the other. I had been playing with BroadVoice which has very good rates, and described the project to their CTO, Nathan Stratton, whom I had met. He offered to provide free global long distance for the week using their network, and a Sipura 1000 adapter.

(In 2006 I used a different company at my own expense.)

All the ATAs have ethernet jacks, though before long we'll see ones with wireless in them too. (Linksys is going to sell a box with a phone adapter, network router, wireless access point and ethernet switch as an all-in-one home gateway. Too bad that's not out yet!) I needed a wireless bridge to convert 802.11 to ethernet. I was lucky enough to find a tiny access point with a client mode by a dead company called TecNew for a whopping $20 in a local surplus store. It was tiny and only draws about 3 watts, just what I needed. In 2006 after finding flaws in its wireless software, I switched to a small Linksys wireless adapter designed to connect wired ethernet devices to wireless networks.

To my surprise, the aluminum of the phone pedestal did not block the signals so I was able to leave the Linksys device inside.

|

| Testing it wireless |

Here are the guts laid out on my floor for the first wireless test. The battery powers the wi-fi box and the SIP box, which is plugged into an ordinary phone. I use my ammeter to see how much power it will end up taking.

Both the Sipura and the wireless bridge run on 5 volts, so I got a DC-DC converter from TI. This remarkable tiny device made me realize how much power supply technology has changed of late. It's able to convert anything from 9 to 36 volts to a clean 5 volts, at 3 amps, more than enough to run all the things in the project, and at 90% efficiency. It's a chip meant for putting on PC boards, but I glued it in a project box and did an ugly soldering job to make the power supply.

|

| Power Supply |

I had thought I might need 12 to 15 watts (some of the earlier equipment I found needed that) but the Sipura only draws 1.8 watts when idle and 2.4 when talking, and the access point only about 2.6 watts as well. Even with the inefficiency of converting, operating the phone would require just 5.8 watts when somebody was talking, and 4.9w when idle! Lighting the phone at night might actually be the biggest draw.

For source power, lead acid batteries give the most bang per buck. Sealed ones won't spill and can be mounted sideways. A standard size for wheelchairs, called a half-U1, fits tightly in the phone pedestal. Each 17 amp-hour battery should provide 37 hours of power if allowed to drain fully, and a full day with a more friendly discharge cycle. I found those on eBay for $15, plus shipping.

We could also have solar powered the phone. That has a certain aesthetic quality to it. The panel need not be that large. If it had enough power to run the phone (Black Rock gets almost constant sun) it would not matter if the phone died late each night to come back to life after sunrise. However, we preferred the batteries to give the aesthetic of an ordinary pay phone.

The pedestal, phone and enclosure are all solid metal, as these are meant to be durable pay phones able to withstand vandals. Bad news for radio signals. We extended a wireless antenna outside the pedestal, and enclosed it in a similarly coloured PVC tube so it would not look so obvious.

The phone needs to be lit at night, to see it, and for safety, and because a real phone is. 5v powered fluorescent lighting taking only about 3 watts was the answer, mounted in the dome of the kiosk. This also makes the sides of the kiosk, which have holes cut in the shape of a phone handset, glow.

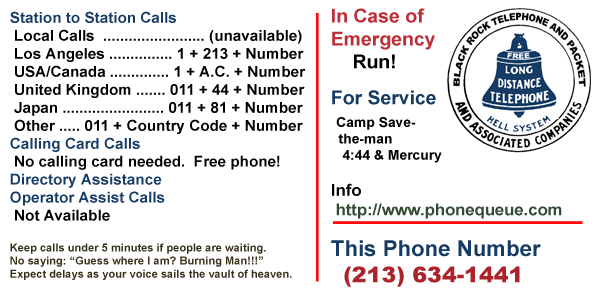

The phone needed its own logos and graphics. For those that don't know Burning Man symbols, the name of the city is Black Rock City (BRC) and thus the SBRC logo. The symbol of Burning Man itself has been morphed into the old Pacific Bell logo. The Bell symbol logo is the 1900 logo of AT&T, but it didn't say "FREE."

Here's the page about actual on-playa experiences.

As noted we didn't get the connectivity that we wanted. Our wireless link was also poorer than expected, perhaps because the wireless bridge and its antenna were not up to scratch. Clearly the antenna could not be buried entirely in the aluminum, but even unobtrusively placing it behind tape or in a plastic tube did not work as well as we would have liked. (Later we were able to move it inside.)

While the Sipura seemed able to decode DTMF and send them out of band, and Broadvoice was able to receive out of band DTMF from other SIP phones I tried, I could not get the two to work together in my experiments. This meant sending touch tones was unreliable. This didn't bother me that much, as I didn't want people to use calling cards, and the phone wasn't really meant to be there as a means to check voice mail -- we wanted interactivity with real people. However, when the upstream was so poor that the other side couldn't hear you, it would have been nice if out of band DTMF had made it possible to do at least that.

The Sipura comes configured to use QOS bits set to the highest priority. We were unsure if the Cisco routing equipment was paying attention to those bits or not, since very little does, but we changed it back to a normal priority. This may have made it work better. The theory is that while you want low latency at the cost of packet loss in some circumstances on the wired net, over a satellite you already have to accept long latency so you might as well get somewhat more reliable delivery of packets.

The real answer would have been traffic shaping in the routers, but there were so many problems in getting the network to work at all that this never made it to the top of the priority list.

While the dish was out, a second network was connected, one run by the Burning Man Corporation that uses a 13 mile 802.11 link to Gerlach to process credit cards. This link, however, was apparently triple-natted, and we were unable to get the SIP link to work over this much natting. Not too surprising, though again in a non-panic environment even this might have been possible.

We also configured the Sipura to send just one voice packet per UDP/IP packet. Due to overhead, this is normally a bad and selfish idea as it increases the total bandwidth needed. However, it means dropped packets drop less voice. Had we had QoS on the phone we would have bumped this to 2 or 3 voice packets (with 20ms of voice each) per UDP packet.

I also brought along a Pulver WiSIP 802.11 phone. This looks just like a cell phone, but as noted there is no art to that. However, it was fun to carry it in my pocket and offer to make calls for people. It faced the same reliability problems. I was also able to configure it to be able to call the pay phone, so a few times when the network was down I used it to call the phone and make joke calls. A very high tech radio if you will.

Surprisingly it worked better at talking to the outside world when natted once than if given an external IP address. I am not sure why that would be. Non-natted 802.11 networks are so rare these days that this may have been assuming one level of NAT. It could not handle the multiple levels of the backup connection.

The WiSIP did work however, and in fact may have had a better 802.11 interface than our aluminum caged phone booth did at times.